Interview: Jack Kausch on Aretalogy (Lineage of a God)

Personal and Philosophical Origins

- Your journey into the esoteric began with a serendipitous encounter with the Corpus Hermeticum. How did that early discovery shape the metaphysical vision we see in Aretalogy?

Actually, it was not the CH! It was this specific book, Philosophorum Praeclara Monita, which I viewed in the Saint Andrews Library. I was particularly taken with the emblematic depictions of planetary metals, which had a deep and powerful effect on my young psyche. From there it was a steady path of reading to other Hermetic pursuits, such as Brian Copenhaver’s translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, which I read at 18. Aretalogy was born out of a decade long engagement with the tradition.

- You describe yourself as an “information ontologist.” How does your academic work in Information Science influence your literary or metaphysical worldview, especially in a book concerned with memory, scrolls, and hidden libraries?

I was always drawn to libraries, but I was also drawn to ontologies. I first learned about ontologies volunteering for the Long Now Foundation on their “manual for civilization” project while I was an undergraduate. This was the first library science work I ever did. Ontologies attracted me because they are a direct application of Neoplatonic philosophy to artificial intelligence and linked open data — many computer science papers cite Porphyry’s tree as “the first ontology.” Thus, I was excited about the prospect of applying the philosophies so close to the heart of my spiritual practice to more secular pursuits, such as organizing documents and graph databases, or helping organizations better manage their data. As far as libraries and memory are concerned, I studied library science at multiple library schools, where I was exposed to the idea of the story of documents, which is that documents themselves are the manner in which we preserve and transmit information. Documents, such as real or imaginary books like the one Psa pursues, have a life of their own, and can transform us as deeply as Philosophorum Praeclara Monita transformed me.

On Aretalogy: Lineage of a God

- Why did you choose to center the narrative on Psammethicus, a marginalized Egyptian scholar navigating Greek Alexandria? Is he a symbolic figure for something larger?

Yes, absolutely. We do not know — not being a historian I am no expert — if any Egyptians worked as scholars at the Musaion of Alexandria, but if there were any, probably they were far outnumbered by Greeks. Psa’s name is a reference to Psamtik I, rendered in Latin as Psammethichus (another feature of Aretalogy is a semi-deliberate mixing of Greek and Latin names, implying that the manuscript is a Rosicrucian memory of Alexandria) who is the first king of the Saite period. This was the period in which the Greeks first began to encounter the Egyptians and their thought more generally, so many of the blanket statements made by writers like Herodotus are emblematic of a very specific part of Egypt’s Late Period. Psa represents Egyptian knowledge as known by Greek eyes, an uncomfortable position in which that knowledge is often exploited, taken out of context, denatured or subordinated — in short Psa represents the ambivalence of the Hermetica themselves, where Egyptian teachings are transformed from their context and presented in Greek form. The Hermetica, like Psa, stand between worlds, being more than just Egyptian, combining Greek, Jewish and (maybe?) Persian elements, but being more than a convenient Greek orientalist forgery as well.

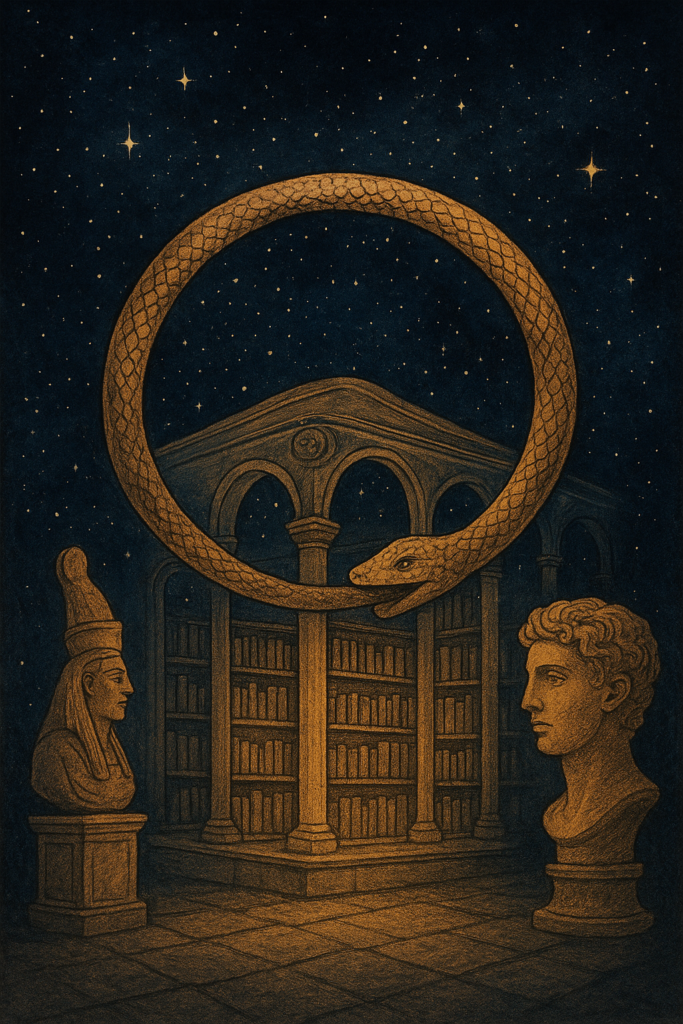

- The book features layered, esoteric conceptions of time — the ouroboric and the linear. How do these models of time relate to your own understanding of history, metaphysics, or memory?

Well, the two forms of time in the novel come from my fictionalization of Jan Assmann’s writings on Neheh and Djet, the first of which is cyclical time which perpetually renews itself, and the second of which is linear time which completes itself by transcending to the afterlife. This is not the same as the way we would think of as linear time, in that it is not sequential. Assmann describes Neheh as existing around the circumference of a circle, perpetually renewing itself with the seasons, whereas Djet is the form of time which runs along the radius from the circumference to the center, where the center is identified with the body of Osiris. It is not like our formless linear time which occurs in a material chain of cause and effect and instead travels directly to a transcendent world where events are already completed. The first half of Aretalogy is written so that the structure of the plot follows the form of Djet, the second, Neheh.

- The character of Hyginos is both absurd and sinister, a populist provocateur cloaked in philosophy. Is he modeled after a particular type of modern intellectual or polemicist?

No, Hyginos is a satire of Greek pederasty. In fact this echoes certain lines from the Stobaean Hermetica which discuss the practices of male love in Greek culture. This is not necessarily a satire of homosexual acts themselves; rather it is meant to put on boorish display the glorification of pederastic love in Greek philosophy as being part of a patriarchal logic that reinforces hypermasculinity while also othering esoteric interpretations of philosophy in favor of purely intellectual ones. Similar arguments (altough not unproblematic) can be found in Egyptian writings of that time.

- The Musaion functions as both a library and a battleground of ideologies. Did you intend it as a metaphor for academic institutions today — and if so, what sides are at war in our current intellectual climate?

I intended the Musaion to be a metaphor for how Greek philosophy appropriated an ideal image of Egypt while simultaneously othering it. This is similar to, but not entirely identical with, orientalism in our modern era. I had no real commentary on contemporary academic institutions in mind when I wrote it. The Musaion or the “Library of Alexandria” is often invoked as an image of the lost legacy of Western culture. Interestingly enough this legacy was located in Egypt, but not of Egypt, in the modern imaginary.

- Psammethicus walks a fine line between multiple identities: Greek, Egyptian, scholar, magician. What does the book say about hybridity, assimilation, and resistance in colonized or cosmopolitan societies?

A major theme in the book is juxtaposing the experience of the Egyptians at the hands of the Greeks with contemporary colonized people — as a beneficiary of North American settler colonialism I have no direct experience of what that is like — but I view the position of Egypt’s colonization as historically important to our contemporary moment because although the colonization occurred over two thousand years ago by different powers with different ideologies, and it would be a gross anachronism to compare it with contemporary European colonialism, still Egypt’s colonization manages to “haunt” Europe, and one of the principle forms of that haunting has been the Hermetica.

- There’s a striking scene where an oracle reveals herself as Seshat. Do you see this as a moment of divine intervention, or psychological insight — or both?

Plutarch writes — here: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/De_defectu_oraculorum*.html — on the mysterious disappearance of Oracles in late antiquity. Which reminds us that at one time this phenomenon was relatively common. The practice of mediumship which is now relegated to roadside psychics was once a prestigious priestly task with its own temple liturgy and rites. There were in Egypt always “wandering magicians” who traveled, unaffiliated with any temple, practicing their craft in some capacity, and I do not think it would be absurd for a goddess to speak through such a medium if they needed to get a message across. Of course, Seshat later has more messages for Psa in the form of the Lamentation of Renpetneferet, which he hears in Hermopolis, and forms the appendix for the book.

- How does the “Library of the Ulterior” function allegorically?

The Library of the Ulterior is a metaphor for the knowledge lost from antiquity. Many of the books described as existing in the library are books mentioned in the fragments of the Pinakes, the Musaion’s Library Catalogue, but which are now lost. Thus it is a metaphor for the act of forgetting knowledge, just as the rest of the book is about memory. It also is a play on the absurdity of cataloguing itself. The point of cataloguing in the Anglo-American tradition is to establish “bibliographic control” whereby the location of books is closely tracked and available when a patron needs them. The experience Psa has of books appearing and disappearing off shelves will be familiar to anyone who ever tried to catalogue or audit a disorganized collection — thus ulterior libraries form wherever texts are lost or forgotten.

- Archimedes plays a key role in the latter part of the narrative. Why did you choose to include this historical figure, and what does he represent in the broader philosophical conflict of the book?

Archimedes is an interesting mathematician and polymath who studied at the Musaion and made several mathematical advancements that would not be taken up again until the Early Modern Period (i.e. Calculus). He was interesting to me because his book on Sphere Making and his theory of integration represent the potential antiquity had to engage in modern ideas (or mathematical errors as the ancients might call them!) but did not. He represents another path that thought could have taken. Also he appropriated the invention of the water screw from the Egyptians, and we have since given that invention his name.

Literary and Structural Questions

- You weave myth, philosophy, comedy, and political satire into a seamless whole. Were you inspired by any particular literary traditions or authors in crafting this blend?

The novel was written while I was halfway through reading John Crowley’s “Love and Sleep” and is intended to be in direct conversation with Crowley’s Aegypt Cycle. I wanted to write a novel actually set *in* Aegypt as a fantasy setting, rather than simply being a metafictional riff on the idea, and one which would engage with the esotericism of the Hermetica directly. I also, like Crowley, greatly appreciate the novels of Thomas Pynchon. However I wanted the novel to read like a YA narrative/bildingsroman in addition to this, and I felt comedy would embody the more pragmatic spirit I believe the ancients took to their philosophies. Comedy forces the reader to question the text they are reading, making them more awake.

- The narrative sometimes feels like a Platonic dialogue, other times like a Kafkaesque farce, and often like a myth in hieroglyphic prose. How do you approach tone and genre when constructing a story like this?

I wanted to use anachronism to make the story more approachable. A tale which tries to be a Platonic dialogue is too dry to appeal to young readers, and I wanted to introduce them to philosophy and myth by making the tone more approachable.

- There’s a recurring question of who gets to record history, and how it’s preserved or distorted. What is your stance on historiography — especially as it relates to cultural erasure and survival?

Well, I think the adage “nothing about us without us” which I first learned from Timnit Gebru will only get more important. Indigenous societies and other marginalized groups have a right to their stories as part of their sovereignty. Ultimately stories should serve the communities from which they come, and they should be told by recognized knowledge keepers in a context in which the community is able to consent to share their teachings.

- Why did you choose to use mythological elements — like oracles, sacred charms, and ghostly visitations — instead of grounding everything in strict historical realism?

Well, where Egypt is concerned, those things are historical realism, regardless of your metaphysical stance on them. You find them described often, and those charms are found all over Egypt’s sacred sites. I wanted to write a fantasy novel where the fantasy was in the real world, and all the magic was real, and it was the kind of magic which actually did happen. Readers may be ignorant of how much magic was part of Egyptian life, but it really did happen.

- Were there any particular scenes or moments that arrived to you in a visionary or dreamlike way, rather than being consciously plotted?

I cannot remember. Most of the book came to me over five days, and I wrote it during those five days, spending ten hours a day writing. It is difficult to distinguish what was me, and what was a visionary experience. Having written it, while the novel makes use of my research and some of my intentions, it often feels like it came from somewhere else and wanted to be born — more so as the years pass on.

Final & Reflective

- If Psammethicus was sitting beside you now, what would you want to ask him?

I believe Psammethicus has told his story. I would like to ask him what is his actual connection with Imhotep. I wonder whether he himself would actually be able to answer that for us.

- What do you hope readers carry with them after finishing Aretalogy?

I want them to take a piece of the ancient world back into our modern era. I hope that this memory, however imperfect, transports them to that time for an instant, so that they can experience that there once was a world that was very very different from the one we live in today, and not just where technology is concerned — ancient people had a very different relationship to the gods than we do today. I want people to remember that that relationship to the gods is still possible, and that there is nothing crazy about it — you can still be a rational, Enlightened, scientific person and worship and honor the gods.

- Are there more stories to come in this world — possibly deeper explorations of the “Library of the Ulterior”?

Perhaps — that is a fun idea. I would enjoy writing fictional versions of lost texts, so long as no one trained an AI with them! I might still like to write a big, epic retelling of the court of Djoser, but so far I have viewed that as beyond my literary abilities. A tale which tells more than just Renpetneferet’s side of the story will someday be needed.