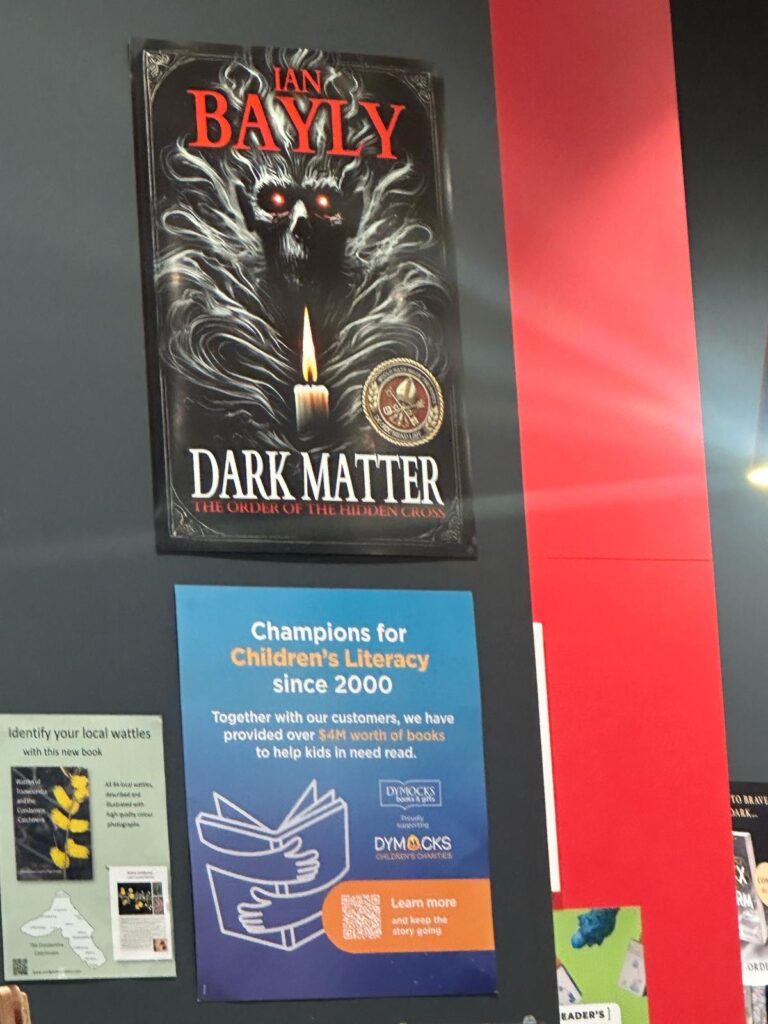

Interview with Ian Bayly: Visiting the Shadows of Dark Matter

- What was the initial spark that led you to write Dark Matter: The Order of the

Hidden Cross?

Back when I ran a bookshop (Maleny Bookshop), I’d meet countless authors launching their latest works. Whenever we talked about success, I’d hear the same aspirations—winning the Man Booker Prize, making the New York Times bestseller list. But I had a different goal.

“If I ever wrote a book,” I’d say, “I’d want it on the Pope’s Do Not Read list.”

That always got a reaction. They’d ask why, and I’d reply, “Because then a billion Catholics would want to know why.”

That thought lingered, simmering in the back of my mind. What kind of book would be controversial enough to earn such a distinction? What would make the Vatican take notice? Dark Matter was my answer. If the Index Librorum Prohibitorum—the Catholic Church’s historical list of banned books—were still around today, I have no doubt Dark Matter would qualify.

- You have a background as a bookshop owner, constantly surrounded by stories.

How did that experience shape your approach to storytelling and world-

building?

To be honest, I wasn’t just surrounded by stories—I was drowning in them. My bookshop specialised in rare and used books, and at its peak, I had over 20,000 unique titles. Every day, I’d pick up something new, flipping through the pages, sometimes enthralled, sometimes thinking, I could do better than this.

One day, someone called me out on it. “If you can do better,” they said, “then stop hiding and write something better.”

That simple. No more excuses.

My storytelling is shaped by the books I lived with—works by authors who didn’t just write stories but crafted entire worlds. Stephen King’s short stories showed me the power of unsettling simplicity. Edgar Allan Poe taught me that the mind’s deepest shadows are the most fascinating places to explore. Dark Matter is a reflection of those influences—blending the eerie, the esoteric, and the deeply human.

- What does the character of Joshua represent to you, and how did you develop his

complexity?

Joshua is, at his core, an alternate-universe take on Jesus Christ. He was born under extraordinary circumstances—just like Christ—but this is a different universe, so naturally, things unravel a little differently.

What makes Joshua complex is what makes all humans complex. Strip away the supernatural abilities, the divine myths, and the pedestals we place people on, and what’s left? A person. A mind tangled in contradictions, trying to understand both himself and the world around him.

We tend to sanctify figures like Jesus, Muhammad, and Buddha, turning them into untouchable ideals. But if we’re really honest, they were just blokes dealing with the problems of their time. They had doubts, fears, and inner conflicts—just like the rest of us.

Joshua is no different. He may have extraordinary abilities, but he’s still broken, still flawed, still searching. And that, to me, makes him more real than any untouchable saviour figure ever could.

- The Order of the Hidden Cross is an organization steeped in mystery and

control. Were there any historical or literary influences that helped shape their

ideology and methods?

This answer might not win me any favours with those billion Catholics, but here we go.

I genuinely believe Paul of Tarsus is history’s first great manipulator—the original wolf in sheep’s clothing. As we Aussies would say, he was a misogynistic mongrel of a bloke. His so-called come to Jesus moment on the road to Damascus? I reckon that was staged. And surrounded by subordinates and slaves who wouldn’t dare challenge him, he was free to rewrite the narrative however he saw fit.

That’s where the Order of the Hidden Cross comes in. I took inspiration from humanity’s need to believe in some secret organisation pulling the strings behind the scenes—a shadowy force to blame for all the world’s woes. The Illuminati is a prime example; despite the fact that its origins as we know them today only took shape in 20th-century Europe, people love to imagine it as some ancient power controlling everything from the Vatican to the local bakery.

We crave villains. We need them to explain the chaos of the world. In Dark Matter, I built a conspiracy around what someone truly desperate for power would do: weaponise fear, control the unknown, and create a pseudo-church that claims to follow Christ’s teachings while, in reality, twisting them into something unrecognisable. Paul, to me, is the blueprint for that kind of deception, and the Order of the Hidden Cross is what happens when those ideals are taken to their darkest extreme.

- Can you expand The Hall of Memories significance in relation to both the

narrative and real-world mystical traditions?

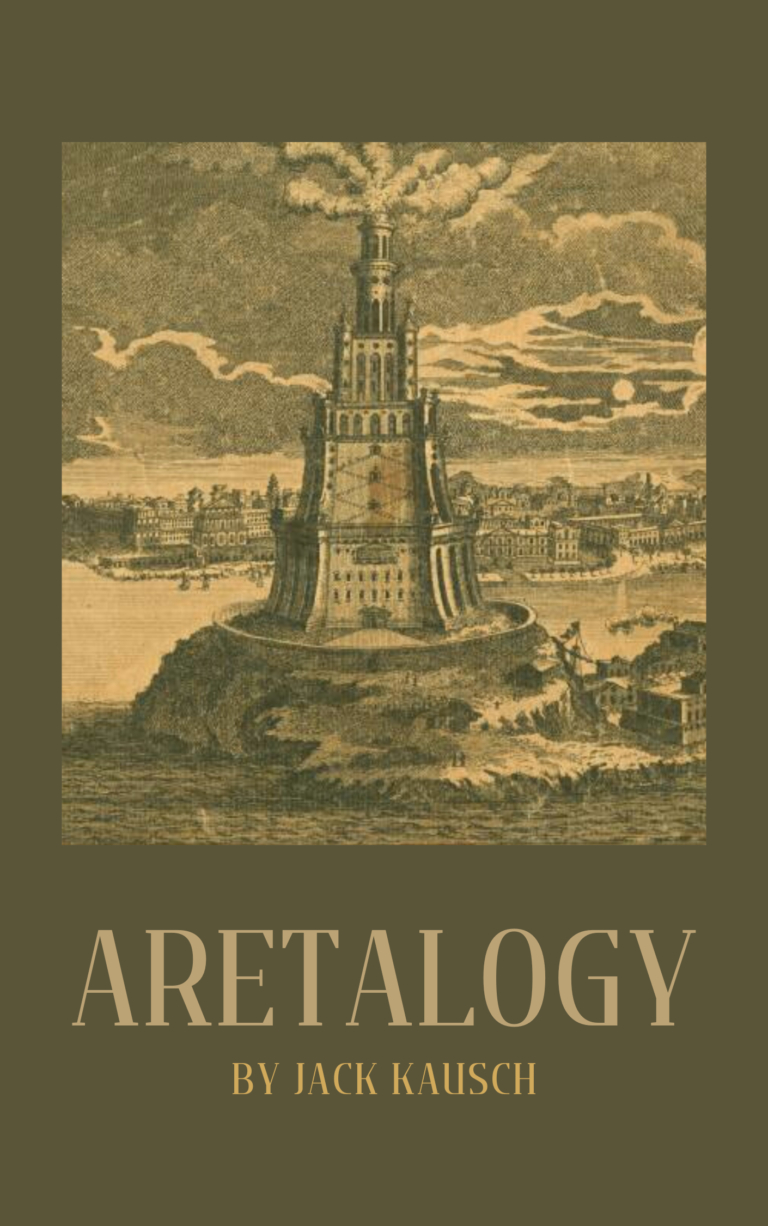

If I’m honest, I’ve always loved the analogy from Conversations with God by Neale Donald Walsch—the one about the little candle in the sun. The idea that without darkness, light cannot know itself. I don’t subscribe to a literal heaven or hell. To me, existence is just experience, and when we die, we return to report back on what we’ve learned—like a cosmic debriefing. Maybe God is in a lab coat, and we’re swirling around in some grand petri dish. Who knows?

But if we are like candles in the sun, unable to see our own light, then wouldn’t God be bound by the same problem? If God is infinite, then God, too, must need contrast—must need the unknown, the forgotten, the dark corners of the mind—to fully grasp its own nature.

That’s what the Hall of Memories represents. It’s not just a library of past lives, nor some dusty archive of forgotten knowledge—it’s the collective record of all things, everywhere. A vast, organic catalogue of every experience across the multiverse, stored and waiting to be accessed by those who seek it. Calling it The Hall of Memories just felt more poetic than calling it The Collective Consciousness. One is a cold theory; the other, a place you can walk through, feel, and lose yourself in.

- Malleck is a fascinating character, walking the line between divine messenger

and infernal entity. What was your process in crafting his ambiguous nature, and

what role does he serve in Joshua’s journey?

This actually leads into a new story (shhh), but at its core, Malleck exists to challenge the idea that righteousness is a shield against consequence. He saves Zivah and Joshua, but that act—no matter how noble—comes at a cost. Rules are rules, and the universe doesn’t make exceptions, even for the well-intentioned.

Malleck is complex because his significance shifts depending on perspective. In his own dimension, he’s a force to be reckoned with. In Joshua’s world, he’s a saviour. But in the Dark Matter—the void between worlds—he’s nothing. That fluidity is key to his character. It’s a reminder that value isn’t fixed; it depends on where you are and what sacrifices you’re willing to make. Malleck serves as both a guide and a warning to Joshua, forcing him to question whether power and purpose are intrinsic, or merely assigned by circumstance.

- Your preface suggests a desire to challenge and provoke rather than simply

entertain. What kind of reaction were you hoping to evoke in your readers?

I want people to stop following like sheeple and start questioning their reality. Not just in some grand existential way, but in the small, everyday moments where we blindly accept what we’re told. Wake up. Look closer. Think critically. Your reality might be different from mine, or it might be the same—I don’t profess to have the answers. But I do know that too many people sleepwalk through life, accepting the narrative they’re given without ever asking, Does this actually make sense?

Wasn’t it Walt Whitman who said, “Be curious, not judgemental”? That’s the heart of it. I want to be curious, and I want others to be too. Dark Matter isn’t here to hand you the truth on a silver platter—it’s here to make you uncomfortable, to make you question, to make you wonder what’s lurking beneath the surface of everything you thought you understood.

- The book engages with philosophical and theological questions, but never at the

expense of the story’s momentum. How do you balance intellectual content with

narrative entertainment?

That ties straight into the last question—I want to entertain, but I also want to plant seeds of doubt, curiosity, and discomfort. My goal was never to be outright offensive, but to offend the mind. To shake people out of their mental autopilot. If a reader walks away questioning something they once took for granted, then I’ve done my job as a storyteller.

At the core of Dark Matter is a fast-paced, gripping narrative, because let’s be real—no one wants to read a philosophical lecture disguised as fiction. The deeper themes are woven into the action, the tension, the moments that make you pause and think, Wait… what if? The trick is never to force the ideas but to let them creep in naturally, through the characters, the choices they make, and the world they inhabit. That way, even when you’re caught up in the suspense, there’s always something lingering beneath the surface, waiting to unsettle you long after you’ve turned the last page.

- Dark Matter raises questions about forbidden knowledge and whether some

truths should remain hidden. Do you believe there are limits to what humanity

should seek to understand?

Absolutely not. I think we’re here to become like gods—or at least to reach for that level of understanding. The world is a playground where we learn to manipulate reality, whether through science, alchemy, or the metaphysical. In that sense, everyone who dares to push the boundaries of knowledge is already playing god. The real tragedy, in my opinion, is those who abdicate that responsibility and simply exist, never questioning, never exploring.

I once met a woman who claimed she had no internal dialogue. That blew my mind. I challenged her on it for a year, waiting for her to slip up, but she never did. She genuinely couldn’t comprehend how I had a voice in my head narrating my thoughts—she actually believed that meant I was possessed, because that’s what her church had told her. That conversation made me rethink reality. How many people out there are just background characters in their own existence? And how many are actually awake, questioning the fabric of it all?

That brings me back to the question—should there be limits? I don’t think so. Are there limits? Hell yes. We are, as a species, deeply unevolved when it comes to wielding true power. No matter how noble we think we are, history proves we almost always choose violence—whether physical or verbal—as our first response to threats. We’re like toddlers handed a matchbook, playing with forces we don’t fully understand. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. It just means we need to grow up fast.

- The prose in Dark Matter is poetic and unsettling. How do you craft your

writing style to enhance the novel’s eerie atmosphere?

I take Walt Whitman’s be curious philosophy to heart. When I write, I don’t censor myself—I get the story out first, raw and unfiltered. The moment I start second-guessing, I risk watering it down. Zivah’s Dream is a prime example. I originally wrote it exactly as I intended, but then I made the mistake of questioning if I’d gone too far. So, I rewrote a tamer version. But then I thought—screw it. If people don’t like it, the book isn’t for them.

Ironically, Zivah’s Dream exists because of a comment from a customer at my bookshop. She told me she hated unnecessary sex scenes in novels—Stephen King was one of her biggest offenders. So, just to be a little petty, I didn’t write a sex scene. Instead, I wrote an entire chapter that is one big sex scene—so visceral it strays into the realm of pornography. Not because I needed to, but because I wanted to push boundaries and challenge that notion of what is “necessary” in storytelling.

At the end of the day, I write the way I want to write. Sometimes it’s poetic, sometimes it’s unsettling, and sometimes it’s just a middle finger to convention. Either way, it’s honest.

I wanted the story to create a level of fear that didn’t just scare people but challenged them—their ideals, their beliefs, their perception of what is safe and sacred. But in reality, it challenged mine.

Writing Dark Matter forced me to confront my own discomforts, my own ingrained limitations. I wasn’t just pushing the reader into dark corners—I was dragging myself there, too. Every chapter was a test: How far will I go? What truths am I willing to lay bare? What am I afraid of admitting, even to myself? The more I wrote, the more I realised that fear isn’t just about monsters or shadows—it’s about what happens when the comfortable lies we tell ourselves start to unravel.

I think that’s why the unsettling elements of Dark Matter feel so real. It’s not just horror for horror’s sake. It’s the creeping dread of what if? What if everything you believed about yourself, your past, your faith, or even your own memories wasn’t true? What if the forces we fear in the dark aren’t lurking to destroy us, but waiting to show us something we’ve spent our whole lives refusing to see?

I wanted to challenge the reader—but I didn’t expect to challenge myself so deeply in the process. And maybe that’s the real power of storytelling. It doesn’t just take you on a journey—it changes you along the way.

- If you could sit down with one historical or fictional figure to discuss the themes

of your book, who would it be and why?

Oh, that’s a tough one—too many choices for too many reasons.

First, Paul of Tarsus—just to ask, WTF? I have serious questions.

Then, there’s Robert Asprin, the author of the MythAdventures series. He played with the idea that demons weren’t hellspawn, just interdimensional travelers, and that concept always stuck with me. I’d love to pick his brain about twisting mythology into something fresh.

Edgar Allan Poe is another. The man was misunderstood. People focus on the darkness in his writing, but I want to understand the madness—where it came from, how he wielded it, and whether he saw it as a curse or a gift. Same goes for Cervantes, who wrote Don Quixote. He did something no one had ever done before—essentially inventing the modern novel. I want to know how he pushed past the belief that everything worth writing had already been written.

Because that’s the thing—I refuse to believe that all ideas have been exhausted. I’d kill to be the first person to introduce a concept that’s never been done before. What a healthy ego I have, right?

- Were there any personal experiences or moments in your life that found their

way into the novel, even in symbolic or metaphorical ways?

Oh, absolutely. I was raised Catholic, so I’ve got the usual guilt complex that comes baked in with that upbringing. But more than that, I’ve had my fair share of bad experiences with the Church—enough that Dark Matter became, in part, a not-so-subtle FU to the institution itself.

I don’t hold back my disdain for hypocrisy, especially when it comes from those who claim moral authority while covering up horrors. If there’s any justice in the universe, every dirty priest who thinks they can wipe their sins clean with a few Hail Marys will one day realise that asking forgiveness from their imaginary friend means nothing. I can only hope they suffer the full weight of their consequences.

So yeah—Dark Matter has its demons, both literal and metaphorical. But some of the real monsters? They walk around in robes and call themselves holy.

- You mention the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in your preface—the Pope’s

historical list of forbidden books. If Dark Matter were to be banned for any

reason, what do you think it would be?

Oh, for so many reasons. In fact, I want it on that list.

- Because it causes critical thinking. And we all know that’s not exactly encouraged in the Church. Asking questions, challenging doctrine—that’s a fast track to heresy in their playbook.

- Because I throw Paul under the bus. I genuinely believe the Catholic Church is not Christian—it’s Paulian. Look at the numbers: a handful of words from Christ, and yet 50% of the New Testament (13 out of 26 books) is written by Paul. The Church isn’t built on Christ’s teachings—it’s built on a throne of lies, carefully crafted to maintain a male-dominated institution that suppresses questioning and obedience at all costs.

I keep coming back to Gandhi’s quote:

“I like your Christ, but I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.”

That sums it up perfectly. The Church—at least the institution—is full of crap, claiming moral superiority while acting in ways that are anything but Christlike. If Dark Matter gets banned for calling that out? Then I know I’ve done something right.

- The idea of duality—light and dark, order and chaos—permeates the book. Do

you personally believe in a balance between these forces, or is that simply a

construct within the story?

Absolutely, I believe you can’t know you’re the light unless you’ve stepped into the darkness. Science struggles to explain darkness—the closest definition we have is “the absence of light.” Then there’s dark matter, an entire force in the universe we know exists but still can’t define. Does that mean we won’t understand these things one day? No. I think we will—just like we discovered fire, just like we cracked the atom. And when that day comes, it’ll be groundbreaking. I can’t wait to see it.

This ties into my views on the devil, angels, and how I think we’ve got the whole thing backwards—not by intent, but by design. Lucifer is never actually identified as the devil in the Bible—not once. And if you really pay attention, the so-called “Devil” never actually lies to mankind. He simply tells the truth and is demonised for it.

Now, do I think the Devil, Satan, or whatever name you want to give him is the good guy? Not at all. But I do think the story we’ve been told is incomplete. Look at the little details—like the stole (the fancy scarf a priest wears during communion). It’s called a sa-tan. Strange spelling, isn’t it? Makes you wonder how many layers of meaning have been twisted, lost, or deliberately rewritten.

Duality is real—but the real question is: who decides which side is which?

- What’s next for you as an author? Will there be more stories within the world of

Dark Matter, or are you looking to explore new themes and narratives?

Right now, I’ve got three books on the go, and I write based on my mood—so which one gets finished first is anyone’s guess. But there’s one in particular that might be my favourite concept yet, and I can’t wait to share it.

Will it connect to Dark Matter? Well, technically, everything I write exists within the same universe—just in ways that might not be obvious at first. But each story will stand on its own. That said, if you pay attention, you might just start seeing the threads that connect them.

I also have a few bigger concepts brewing—stories that I know I’m not quite ready to write yet. Some ideas need time. Some stories need a more experienced writer to do them justice. So, for now, I let them simmer, knowing that when the time is right, they’ll demand to be told.